The Flow and Knytt Stories

March 31st, 2010For one of my classes, I have to do a blog post weekly based on some reading we are assigned. We had the option to set up a blog on wordpress.com for this purpose, but since I already have a blog, I might as well use it! Plus, I get some motivation to draw comics that accompany my blog post responses, so at the very least, maybe it will make grading a bit more interesting for the TA.

This week, we were assigned to read chapters 3 and 4 of “The Flow” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and “Why We Play Games” by Nicole Lazzaro of XEO Design.

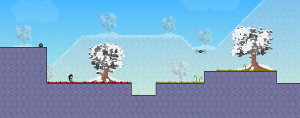

While reading Csikszentmihalyi’s description of what flow is, my mind immediately thought of a particular game I played a lot in my freshman and sophomore years of college — Knytt Stories. Knytt Stories is by an independent developer, Nifflas, who is known for his non-linear puzzle platformers that provide amazing atmosphere and ambience, despite fairly simple graphics (the awesome background music for his games is probably a factor in this). Knytt Stories is no exception.

From the moment I first tried playing it, I was hooked — the controls were simple and intuitive, so that I really felt that I was one with the main character (a little wall-climbing creature named Juni). She did what I did, I did what she did, and as a result I felt frustration, fear, and triumph as I played through the levels. Also, one of the major aspects of the Knytt Stories game is its environment. While playing through the puzzle levels, you may stumble across a part of the level that is no obstacle, but offers no progress, so that you wonder, “why is this part of the level here?” Instead, you might see a little animation — a creature walking into its house, a flower blooming from the ground, a bird preening itself on a branch. The Knytt Stories world is not always practical, and the player is left with a sense of wonder even as he completes a level. Often, there are in fact many different ways to “beat” the level. In this way, Knytt Stories provides a world that invites exploration, both spatially and with respect to decisions. The world could be immersive and aimless if I wanted to be, or, I could return the rules at will and continue in my quest for completing the level.

Though I was “busy” with schoolwork and extracurricular activities, I still found time to play this game. In fact, the only reason I stopped playing Knytt Stories was because I ran out of levels to play (though, there is a new expansion pack out that may start me on the path to addiction… again). The in-game environment itself was so immersive that I could play even while friends were playing console games or watching TV in the same room, or while knowing that I had an assignment due later in the week. The little world’s incompleteness, whimsicality, and simplicity had the power to command my attention — not just while I was playing the game, but also during other times of day (characterized by thoughts of how to beat the next level, or even simply when planning out when I would play the game next).

Though Lazzaro does not explicitly talk about The Flow in her abstract, it seems to me that people play games because it is a flow activity for them; the description by Lazzaro of how people play games contains the elements of enjoyment laid out by Csikszentmihalyi (challenge, merging of action of awareness, clear goals and clear feedback, concentration on the current task, a sense of control, a loss of consciousness of self, and the transformation of time). Therefore, as Lazzaro says, people play games “not so much for the game itself as for the experience the game creates”. The game offers a challenge from which we can emerge triumphant, more skilled, and with better self esteem. It offers rules and a world that we can understand and feel in control of, and allows us (just like a good book!) to go places we would not normally be able to go and do and see things we would not normally be able to do and see.

RSS

RSS

That game sounds like a great game to pull someone into the flow! I feel like your connection with the character as well as the simple controls really pull you into the game and instead of it feeling like a game, it feels like real life. And the fact that there are many different ways to beat a level expands upon your creativity and helps you achieve that balance between challenge and kill level needed to get into the flow.

While I’m not a big fan of these types of games I have several friends who play/design platform games that seem somewhat like Knytt Stories. I’ve never really been too interested in this category of games, but my friends (who I’ve seen spend hours at a time on even a single level) had explained that they liked the games because they enjoyed being “in-tune” with the game world, and, as you mentioned, being left with a sense of wonder even if the game world isn’t always practical.

I think our differences in opinion and what it requires of games can be explained by a difference of “keys”, mentioned in particular by Lazzaro, that different games “bank” on to draw your attention into the game.

After reading this post, I downloaded that game. Yes, it is pretty addictive, and it’s a great example of a game where the appeal comes from the gameplay rather than the story. It almost reminded me of Tetris — the graphics were pretty basic and repetitive, but you didn’t really pay attention to them. The character designs and graphics are all minimalistic, letting you focus on the interaction between the (rather tiny) avatar and the game elements. I think I got stuck in the black mossy level, though. Too bad I only get one save point…

I’m kind of surprised that you didn’t mention drawing graphic novels, given that you’re an officer in UW’s Graphic Novel Society :-P. While the game was definitely more related to the class, I wonder if you get a similar feeling of total immersion when you’re bringing characters to life on paper. After all, that’s what I’m seeking to do, for both myself and my readers — it’s part of the reason I trudge to HUB 304F on Fridays. Would you say that reading and/or drawing comics draws you into “the flow”, or is it just too tedious and time-consuming?

Webcomics definitely make things more fun when grading! I’m so glad you focused on Knytt stories – what a great game. And I’m glad you saw a connection between the Lazzaro article and the two Csikszentmihalyi articles – your parallels did not go unnoticed (:

After reading this, I had to go try out Knytt Stories too. So far, I have all the power-ups except the hologram. It was really good! Except, after I got the invisible eye and the umbrella, I got lost. I’ll have to figure that out. And after I do, there are two more expansion levels, and it looks like there’s a huge archive of player-created levels…

The quote you chose from Lazzaro gets straight to the point. The experience of the game is the thing that we get hooked on – in fact, it’s probably the only aspect of the game which is persistently “real” for us. It also sounds like you do a lot of thinking about design while you play, the “why is this here” question is an important one, because someone deliberately or casually designed every element in the virtual world. Maybe you’ve been conscious of making similar decisions while drawing?

First, I would like to congratulate you on having the most engaging introduction into a post for this assignment, or any other other assignment, that I have seen. Furthermore, the unique structure of your post, in that you did not simply follow the prompt in organization and instead addressed it in a unique and personalized manner, made it quite engaging to read.

With regard to content, I found it especially interesting that a game with such simple graphics (judging by the screenshot and your own description) could be so absorbing in terms of gaming. Such an experience of “flow” dispels the stereotype that increased realism within a game makes it more engaging and/or “flow”-promoting. This counter-example is supported by your skillful use of a direct quote from Lazarro that addresses the exact manner in which you are able to engage with this game through your own mechanisms rather than relying on some intrinsic part of the game itself.

I find it interesting that while I had considered environment from the perspective of what was actually around me while I was engaged in an activity, you considered environment from what was created by the activity itself. While the outside environment appears to have little importance in achieving a flow state, the mental environment is crucial. It seems a person really has to get immersed into the activity to experience flow and I think you’ve definitely demonstrated being immersed.

Going to go try Knytt Stories. You had me at “the controls were simple and intuitive, so that I really felt that I was one with the main character.” I’m a sucker for intuitive.

P.S. I fully support further web comics.